Stay always informed

Interested in our articles? Get the latest information and analysis straight to your email. Sign up for our newsletter.

The association of European employers, BusinessEurope, is the most active and probably the most powerful lobby group in the EU institutions. Determined to see the EU adopt policies that defend profits over people and planet, they have won privileged access to decision-makers like no other and even shape the direction of the EU as a whole. It is high time to roll back their power and privileged access.

For its sheer firepower and ability to strategize across sectors, BusinessEurope (BE), is the Death Star of corporate lobbyists in Brussels. Active on almost all issues of interest to industry, BusinessEurope has an unquestionable impact on not just EU laws – big and small – but on the development of the European project as a whole.

While corporate lobbyists operating at the heart of the EU come in all shapes and sizes – from individual companies acting on their own, to associations manoeuvring to fight for an industry, to temporary or permanent coalitions of like-minded sectors – BusinessEurope is operating on another level. It claims to represent more than 20 million companies of all sizes and in all sectors, and is one of a handful of corporate lobbyists in Brussels with special status, as the confederation of national employers’ federations with 40 member organisations from all member states and beyond, including Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie (BDI) from Germany, and Mouvement des Entreprise de France (MEDEF, France).

The organisation is at the centre of business strategising on EU affairs. It is a major force in pushing for a European economy structured around economic freedoms through Single Market legislation, with little regard for their adverse social and environmental consequences. It has been at the forefront of the so-called ‘Better Regulation agenda’ which actually removes regulations for companies. It was a staunch supporter of austerity policies and attacks on labour rights and social rights during the euro crisis from 2010-2015, and it has insisted on keeping wages down and cutting pensions via EU procedures ever since. And it has always been hostile to policies to tackle climate change – so much so that in 2015, 25 global institutional investors asked 9 big companies to pull out of BusinessEurope entirely due to its poor record on global warming. If in more recent years it has shifted its messaging slightly, it largely because the current EU climate strategy includes a plethora of industry-friendly measures, including emissions trading, prioritisation of gas, and more generally an insistence that measures to protect the climate have to be supportive of growth and competitiveness of European businesses. This is a testimony not to the credibility of such measures, but to the power of business, not least of BusinessEurope.

The most active lobby group

While it may not always be the most visible player on the lobbying scene, it is almost omnipresent. That’s why it’s so important to keep monitoring the strategies of BusinessEurope, exploring its toolbox, and assessing its strength. It has both capacity and opportunity to meet constantly with decision-makers, and that is only at the top layer; there are myriad more, less visible paths for influence. And in recent years its lobbying firepower has certainly not decreased.

According to LobbyFacts, BusinessEurope is the organisation with the most meetings with the European Commissioners and their most senior civil servants, the cabinets. Since 2014, BE has had a total of 402 meetings at that level, 145 of them with Commissioners (August 2023). Since von der Leyen took over as Commission President in December 2019, BE has had 87 meetings with Commissioners and 107 with members of their cabinet (as of August 2023).

Clearly BE is a regular visitor with the Commission and high-level civil servants; and these numbers are not even complete. The register only covers the Commissioners and the top 300 officials, which leaves out a large number of civil servants actively involved in policy-making. Moreover, not all meetings with Commissioners and high-ranking civil servants go into the register, ie those held in the context of the Social Dialogue, a series of procedures which allows the ETUC, the trade union confederation, and three employers’ associations – SGI, SMEUnited, and BusinessEurope – to be thoroughly consulted in social affairs and labour market issues.

Finally, according to Integrity Watch, BusinessEurope has had more than 100 meetings with Members of the European Parliament since June 2019, which makes them virtually part of the furniture. And in reality the number is likely to be even higher, as not all MEPs disclose their lobbying meetings.

Coordination and distribution

A full account would also have to include BE’s role as a coordinator between employers, one that can help distribute resources towards the most important issue of the day.

While BusinessEurope tends to have a strong opinion about everything economic, its main task is to fight for employers’ interests in overarching and strategic areas, including the Single Market, economic policies, labour markets, education, and more. For example it often fights for less – or laxer – regulation generally, as opposed to in specific sectors such as chemicals. However, BE will step in when an issue that mainly affects a particular sector becomes high on the political and economic agenda. For instance, in 2017 it was quick to pick up the fight to prevent platform workers from having easy access to labour rights enjoyed by other workers. The platform companies, such as Uber, were clearly too weak to win on their own. BE happily provided support, and has since become the strongest opponent of mandatory EU rules in this area.

Given BE is an umbrella organisation for the most important employers’ groups in Europe, it facilitates close cooperation between the 40 member groups. Very often one or more member organisations take the lead on a particular issue and reports back to BE, in order to have the organisation as a whole intervene and contribute, to strategise with allies, and to pool resources. For example when two Nordic employers groups launched a campaign against sustainable corporate governance and due diligence in 2020-2021 out of fear that their boards or directors would become liable for human rights atrocities or environmental destruction committed by their subsidiaries or suppliers abroad, as a first step they reached out to BE to set up an active coalition and improve coordination. The campaign was very successful. In terms of how many companies in Europe, and how far down the supply chains the rules would have an impact, and indeed the measures and their enforcement, the final proposal from the Commission was far weaker than originally envisioned.

More than meets the eye

It’s this cross-sector strategising role that makes BE a kind of Death Star – a coordination centre and a pool of resources – for big business lobbyists in Brussels. Given this, it makes sense to add the meetings between the Commission and the individual members of BE to get a real sense of the firepower involved. And that brings us to another level entirely. According to the European Commission’s Transparency Register, during the von der Leyen presidency, BE’s member organisations had a total of 152 meetings with Commissioners, adding to the 87 by BE, and a further 228 meetings with cabinet members. There are a few overlaps with the BE meetings, but not a lot. (A comparison between the 402 BE meetings with Commissioners and cabinet members, with 168 meetings of the German Industry Association Verband der Deutschen Industrie show that only 4 overlap.)

If we apply the same logic to the lobby spend and number of lobbyists, that is, adding the member organisations’ numbers to those of BusinessEurope, we start to get a real idea of the combined firepower. According to its own entry to the Transparency Register, BE spends between €4 and €4.5 million per year employing 30 full time lobbyists. If we add the member organisations, however, the total sum is between €22 and €26 million, and the number of lobbyists is between 215 and 380.

A caveat: these numbers are still likely to be underestimates. According to BE’s website, it has a total of 57 employees, and according to the company register of the Belgian National Bank, it has an annual turnover of approximately €9.3 million euros, more than double the sum of 4 million euros it has reported as lobbying expenses to the Transparency Register. We’d argue that given the organisation’s whole purpose is to influence the EU institutions – to lobby - BE’s Transparency Register declaration of its own lobbying firepower seems rather conservative.

The Commission comes to them

The high number of meetings is about much more than a visit to a Commissioner’s office. Frequently, Commissioners or cabinet members come visit the employers’ headquarters in Avenue Kortenbergh, or join internal meetings online. For example in the spring and summer of 2020 members of Commissioner Reynders’ cabinet joined several meetings of BusinessEurope’s Legal Affairs Committee to discuss the Commissioner's plans on corporate governance. And on occasion Commissioner Nickolas Schmit has been part of the talks when BusinessEurope’s Social Affairs Committee met, as in a June 2020 discussion about posted workers (ie. workers that work temporarily in another member state) and the directive on minimum wage that he was still mulling at the time. In November 2022 Kurt van den Berghe, member of Commission President von der Leyen’s cabinet, joined a meeting of BusinessEurope’s Industrial Affairs Committee to discuss the energy crisis and the European Green Deal.

The more powerful the Commissioner, the more BusinessEurope’s dominance on the lobbying scene stands out. And BE has regular interaction with all the key figures in the Commission. The exception is to some extent the Commission’s President who seems to have a strong preference for the European Roundtable for Industry – a forum of dozens of leaders of the biggest transnational companies in Europe. However, when including the cabinet, BE stands out as the most frequent visitor in the President’s office with a total of 14 meetings since December 2019. In comparison, the ETUC, the trade union counterpart, met von der Leyen’s cabinet only twice, at meetings where BE too was present.

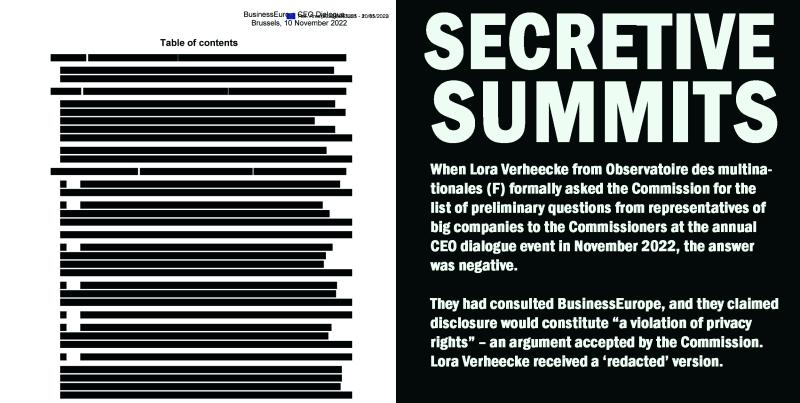

The annual secretive summit

Perhaps the strongest indication of BusinessEurope’s strong relationship with the European Commission is it at its annual get-together. In November each year BE organizes a conference for its Advisory and Support Group (ASG) - an assembly for big companies inside BusinessEurope that do not formally have a vote in the formal BE decision-making. That does not mean, however, that they do not have a say, nor that they are not integrated in the daily business. Uber, for instance, is represented directly in the ASG and indirectly in relevant BusinessEurope committees via allies from other companies or associations they are a part of. The annual “CEO Dialogue” with the Commission, then, is more a sign of an extraordinary status these companies enjoy with BusinessEurope, and the Commission.

The basic concept seems to mimic the annual meeting between the President of the Commission, the French and German heads of state and the chief executives of mega-companies in the European Roundtable for Industry (ERT) – a summit between political and economic power. As with the ERT Summits, the meetings between the Commission and BE’s ASG, the hottest economic issues of the day are discussed. But the meetings are clearly not intended for publicity. Both the Commission and BusinessEurope are shy about sharing details from the conversations between some of the biggest companies in Europe and Commissioners.

It is supposed to be very high level on both sides. That is reflected in the list of companies in the Advisory and Support Group (see box), which includes companies from sectors the Commission should sever its ties with, including tobacco companies, whose lobbying is covered by global rules that obliges decision-makers to reduce their interaction with them. Furthermore, the list includes gas and oil companies, which in a time of climate crisis should be covered by rules along the same lines.

Still, the list of Commissioners present at the ASG meetings shows no consideration of this sort. There is massive support by the Commission for these encounters. In 2021 the annual CEO dialogue was joined by Commissioners Dombrovskis (Vice President), Kadri Simson (Energy), Mairead McGuiness (Financial Services), Thierry Breton (the Single Market), as well as by Diederik Samson from Frans Timmermans’ cabinet. In 2022 the guest list was no less impressive

with four Commissioners in the programme: President von der Leyen, Valdis Dombrovskis, Margrethe Vestager (competition), and Gentiloni (economy). No other private organisation is able to attract this number of Commissioners to a meeting. Also, several of the meetings take place in the Commission’s own Berlaymont building – a strong sign of the close links between BusinessEurope and the European executive.

The Commission’s ‘experts’

There is but a small step from the privileged access BE enjoys, to its role as an adviser rather than a lobby group for vested interests, and indeed BE is frequently invited to assist the Commission in that capacity. According to its own entry to the Transparency Register, BE has members of 34 of the Commission’s so-called Expert Groups. These groups are set up to assist the Commission in its work, and the most important ones actually help the Commission draft legislative proposals.

Some of the 34 groups see BE act alongside organisations that represent other interests, be they consumer associations, environmental groups, or trade unions, but in many cases, business interests dominate the forum. For example the ‘Industrial Forum’ is set up to “assess the risks and needs of industry as it embarks on the twin, green and digital, transition”. Though such a broad agenda ought to call for input from various interest groups, the Industrial Forum is dominated by business, including BusinessEurope. In the Industrial Forum only one trade union organisation (IndustriAll) and two environmental groups are isolated amidst a sea of 31 business associations. This pattern of business dominance, with business heavily outnumbering other interest groups, is repeated in groups on public procurement, fluorinated green-house gasses, economic migration, industrial emissions, sustainable finance, raw materials, standardization, VAT, cross-border taxation, and aggressive tax planning. All in all 16 of the 34 expert groups BE participates in are dominated by business groups.

Discussion partners of the Council

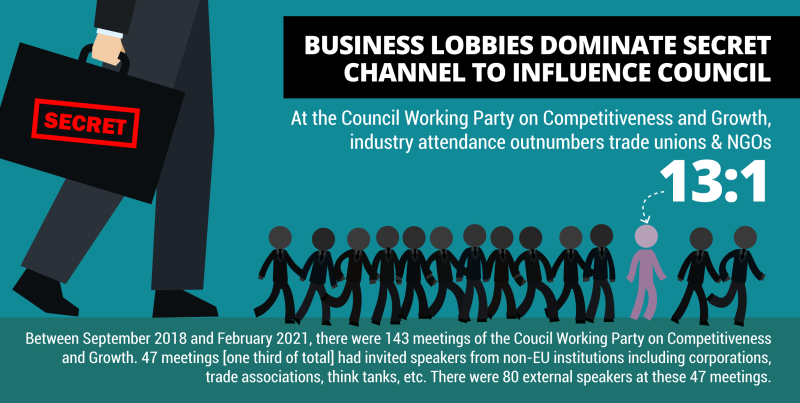

This pattern is repeated, albeit in a less comprehensive or perhaps less transparent way, in the Council’s Working Parties, including the bodies responsible for preparing ministerial meetings and political compromises. It is clear that BusinessEurope frequently appears as speakers at meetings particularly relevant to them, although the scale is difficult to pinpoint, because there is less transparency around Council groups than with the Commission’s expert groups.

Participation in advisory bodies, either as advisers as in the case of Commission expert groups or as regular guests as with Council preparatory bodies, allows BusinessEurope to participate in important stages of decision-making. Proposals are prepared with the Commission, and the position of governments are discussed and often negotiated in the Council preparatory groups.

This dynamic puts employers on top of events. For example the work of the Industrial Forum expert group is closely linked to the work done by the Working Party on Competitiveness in the Council. Here, the tradition is that BusinessEurope is often invited, as on 13 February 2023 when it and SMEUnited were asked to speak on the topic, “What is needed from better regulation to support competitiveness?” Such a visit is not unusual. According to a count from July 2021, in the Working Party on Competitiveness and Growth which often addresses cross-cutting strategic matters, business representatives are 13 times more likely to be invited to a meeting than a trade union organisation or an NGO, and BusinessEurope comes out on top as the most frequent guest speaker.

But BusinessEurope can do much more than speak to civil servants that prepare a Council meeting. It is becoming tradition that shortly before a new government takes over the presidency of the Council, key ministers meet with the Council of Presidents of the 40 member associations of BusinessEurope to discuss priorities. This happened both with the Czech Presidency (second half of 2022), the Swedish Presidency (first half of 2023) and the Spanish Presidency (second half of 2023).

The reluctant social partner

A final factor that counts in the balance sheet of BusinessEurope’s assets on the EU lobbying scene is its status as a ‘social partner’ along with SGI (public employers), SMEUnited, and the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC). Under this rubric, BE participates in official committees which discuss or negotiate agreements between the ‘social partners’, which are consulted by the Commission on files particularly relevant to them before anyone else is asked.

Besides exclusive consultation, the other privilege of the social partners is to have agreements concluded among them, mainly between BE and the ETUC, elevated to EU law with help from the Commission. In recent years this has barely happened as the Commission has proved reluctant to follow the lead of ‘social partners’. That in turn has led many academic observers to conclude that the ‘social dialogue’ is in a deep crisis, if not dying or becoming obsolete.

BE’s status as a social partner should not lead anyone to believe that the organisation has any kind of social agenda for the European Union. Rather BE uses the privileges of being a social partner to fight for employers’ interests in that setting, as with a reply written collectively by all three employer organisations to the European Commission in October 2022 in the context of preparing recommendations to Member States on their economic policies and the plans of the EU.

This was when Europe was suffering from high inflation and soaring energy prices, undermining wages and exposing a severe level of energy poverty in large parts of the EU. On this occasion, BE, SMEUnited, and SGI issued warnings against “a dangerous wage-price spiral” at a time when consensus was building that wages were not the source of inflation – abnormal profits were.

As for the role of social partners in the reform strategy proposed in the document, it is the hope of the employers to get the support of trade unions to secure “the sustainability of social protection systems”, to address skills shortages and education, and to design support schemes for enterprises “that are impacted negatively by the green transition”. On this and on countless other occasions, the contribution to social dialogue, then, is by and large a request from the employers to get the assistance of trade unions and of the Commission to carry out reforms that are in the interest of employers, not a social agenda seeking to mitigate the horrendous undermining of workers living standards at a time of crisis.

The end of privileges

We stand amidst a climate crisis and a social crisis, and if we add to that the increasing bureaucratization of EU politics on economic policies – the obscure procedures of the European Semester where pressure is regularly brought on member states to reform labour law or cut pensions - the power BusinessEurope wields is a major challenge. The corporate lobby group is inherently myopic in its worldview, inevitably putting profits before planet and people. It has incessantly created obstacles to climate policies, and it will continue to fight tooth and nail to prevent the EU from becoming anything like the ‘Social Europe’ trade unions have talked of for decades.

That’s why it’s time to rid BusinessEurope of its status as a red-carpet lobbyist. It has to come to see itself as something of an institution in EU politics, whether by priding itself as a representative of business, or as a ‘social partner’, and it has steadily won ever more privileged access to decision-makers. In view of the major social and environmental challenges we face, it is high time we begin rolling back the red carpet.

The measures needed are:

These reforms would not solve the issue of undue corporate influence in the EU, but they would be a good start. And they are long overdue.